This month, the theme is Family Matters. I think family dynamics make for great reading and it’s interesting to read about situations that can be similar enough to your own to feel familiar yet different enough to make you feel like you’ve stepped into another life for a while. Regardless of how you define your family, it is often through these relationships that we learn to navigate our world and understand ourselves in relation to others. For May I have tried to choose works that explore notions of family in unexpected ways.

If you look at the list and it seems like I’ve added an extra weekend to May (I wish), I am trying to make up for lost time. There have been two weeks since I started this challenge that I didn’t make my reading goal, so I am going to add a book this month and next to get back on track (32 down … 20 more to go). Wish me luck.

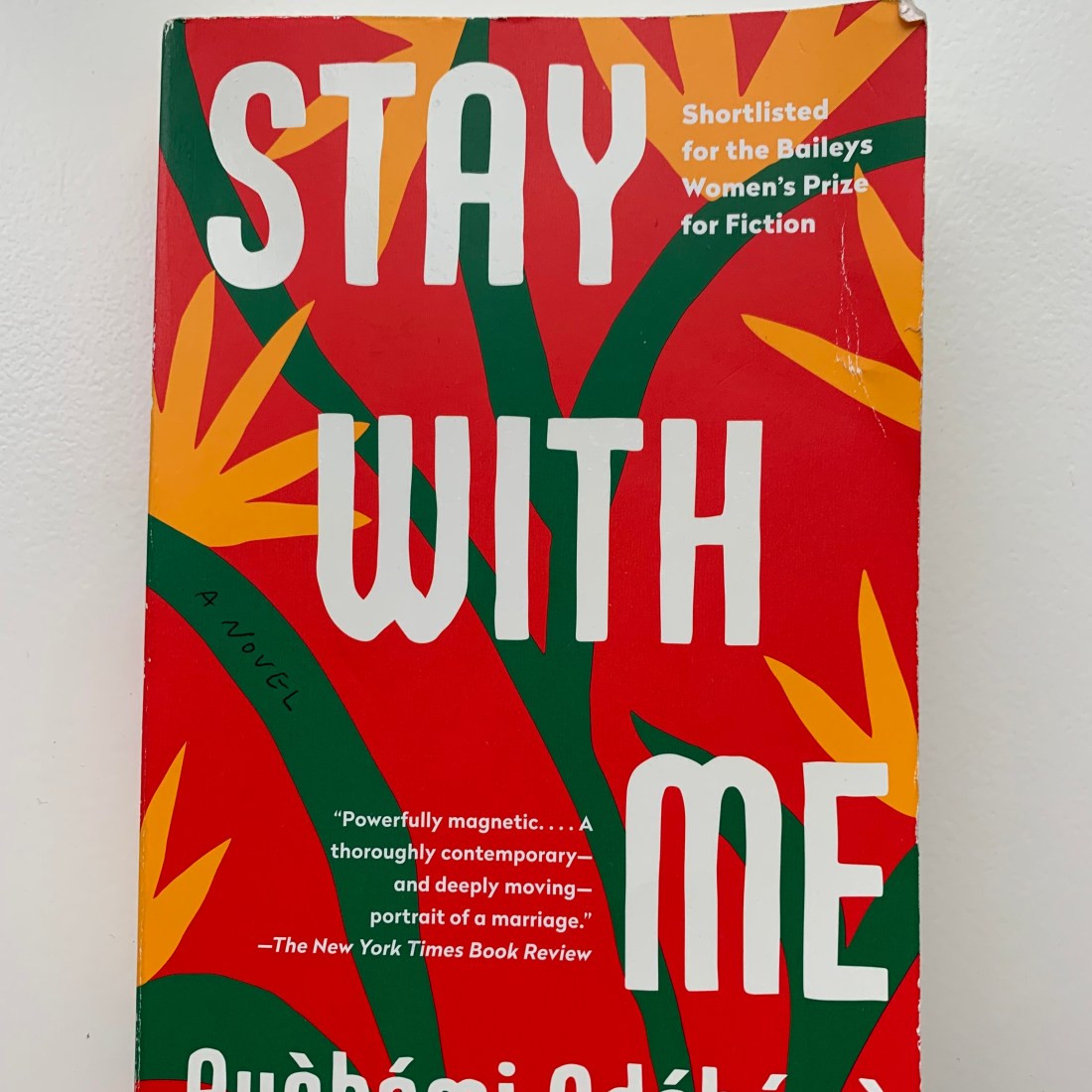

May 4, 2019: Stay With Me by Ayobami Adebayo

Since discovering Chimamanda Adiche, I feel like my eyes have been opened to all this great fiction coming out of Nigeria. Recommended by one of my colleagues, Adebayo is a new author to me. The novel is set in Ilesa, Nigeria and follows the relationship of a couple who seem like they should be happy and secure in their marriage. Despite being deeply in love, Yejide and Akin are unable to have a child. The increasing pressure put on the couple to have a family begins to test the strength of the marriage. When Akin is coerced into taking a second wife, Yejide knows that she must get pregnant at any cost in order to save her marriage. Before picking up this book I hadn’t realized that polygamy used to be common practice in Nigeria; although it doesn’t seem to have had the same religious connection that it has in other cultures and I will admit that I am very curious about how it plays out on the page.

May 11, 2019: The Almost Sisters by Joshilyn Jackson

Leia Birch Briggs is a comic book artist. She is also 38 and pregnant for the first time. The father is an anonymous Batman she met at a comi-con. Before Leia can tell her traditional Alabama family about her impending single-motherhood, her stepsister Rachel’s marriage falls apart. To add to the chaos, Leia’s beloved grandmother begins suffering from dementia and Leia must return home to help her put her affairs in order. Jackson’s writing sounds witty and has that wry sense of humour that I like with the added bonus of inter-generational family drama.

May 18, 2019: The One-in-a-Million Boy by Monica Wood

Ona is 104 years old. Every Saturday morning, an eleven year old boy comes to help her out. As he goes about his chores, Ona finds herself telling him the story of her life including secrets she’s held on to for years. One morning, the boy doesn’t show up and Ona thinks perhaps he wasn’t the person she believed him to be. But then the boy’s father arrives, determined to finish his son’s work, and his mother isn’t far behind. I have a feeling this one is going to be a bit of a heart breaker…

May 25, 2019: Dress Your Family in Corduroy and Denim by David Sedaris

Despite hearing his name probably dozens of times, I’ve never read anything by David Sedaris. He’s a regular contributor to NPR’s This American Life (again, heard great things but I’ve never listened myself). In this collection of essays, he recounts stories from his own family that show the absurdity in the everyday. Sedaris is one of the most renowned humour writers in America today so if you love to laugh, you might want to read along with this one.

May 31, 2019: A Place for Us by Fatima Farheen Mirza

A wedding is often a time for families to come together and it serves as the linchpin for Mirza’s debut novel. Hadia, the daughter of an Indian Muslim family, is getting married but as everyone gathers for the wedding, the focus is not on Hadia so much as her estranged younger brother, Amar, who is returning to the family fold for the first time in three years. The novel delves into the family’s tensions and secrets that drove a wedge between them as they struggle to try to find their way back to each other.

One of my favourite things about blogging about books is the conversations I get to have with other readers. I love hearing what others are reading. So now that you know what I’ll be reading for May, it’s your turn – what’s next in your TBR pile? Let me know if there is anything you think I should add to my summer reading list!