The theme this month is, “Might I Recommend?” I love book recommendations because often the books that get recommended to me are not ones I would have picked up on my own. I’m lucky to have friends, family and coworkers with great taste in reading so I never have to look very far for my next read. Lately (and against my better judgement) I have also started listening to the podcast, What Should I Read Next? Somehow, the host, Anne Bogel, is living my best life. On her show, she interviews people who engage in what she calls, “the reading life”. At the end of each interview – and this is the part where I should really hit stop but I never do – she asks her guests for three books they loved and one book they hated and from there, she recommends other books she thinks they would enjoy. And I literally sit there listening with my Amazon app open. It’s not a good scene. Well, with those personal demons unleashed, here is this month’s line up:

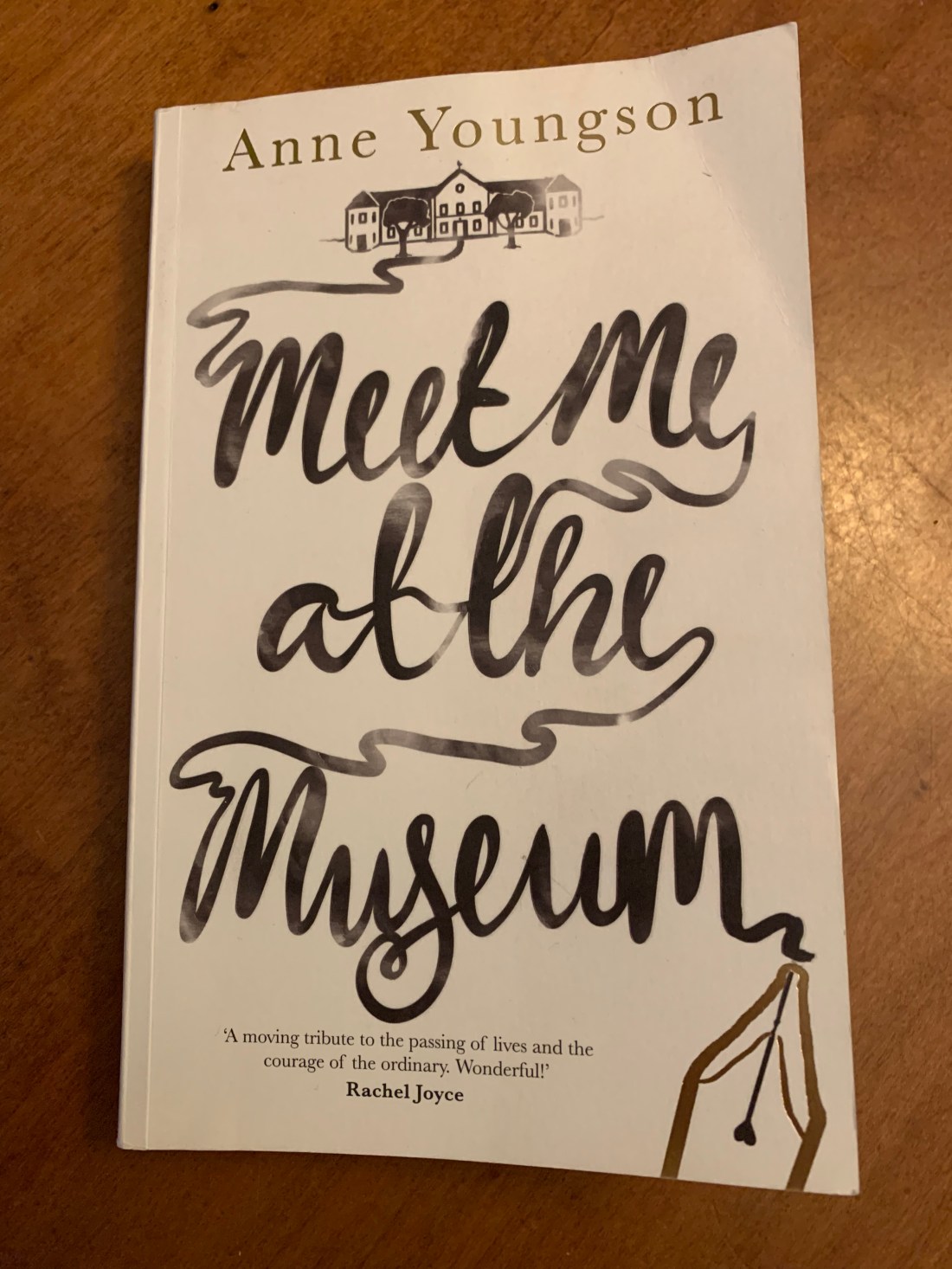

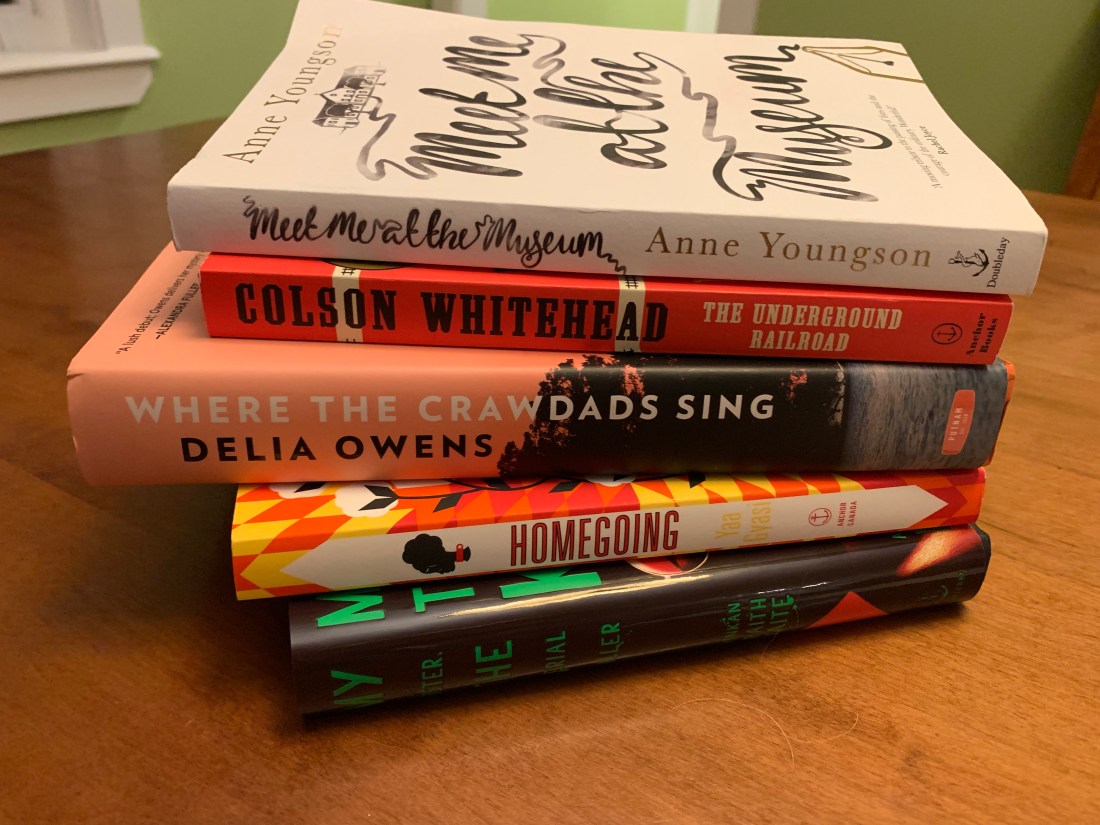

March 2, 2019: Meet Me at the Museum by Anne Youngson

Anne Bogol has recommended Meet Me at the Museum twice in recent episodes. It is a novel written in letters between Tina Hopgood, an elderly farmer’s wife from England, and Anders Larsen, a Danish museum curator. When Tina sends a letter to a man now long dead, she gets an unexpected response from Anders. Both of them are searching to make sense of their lives – Tina married young and never did the things she dreamed of as a girl; Anders has lost his wife, as well as his hopes for the future. Through their exchange of letters, their friendship grows and then Tina’s letters suddenly stop. Oddly, their friendship begins with their mutual interest in The Tollund Man, a preserved body unearthed in a peat bog in Denmark in 1950. This novel seems to have just the right amount of quirkiness to pique my interest right now.

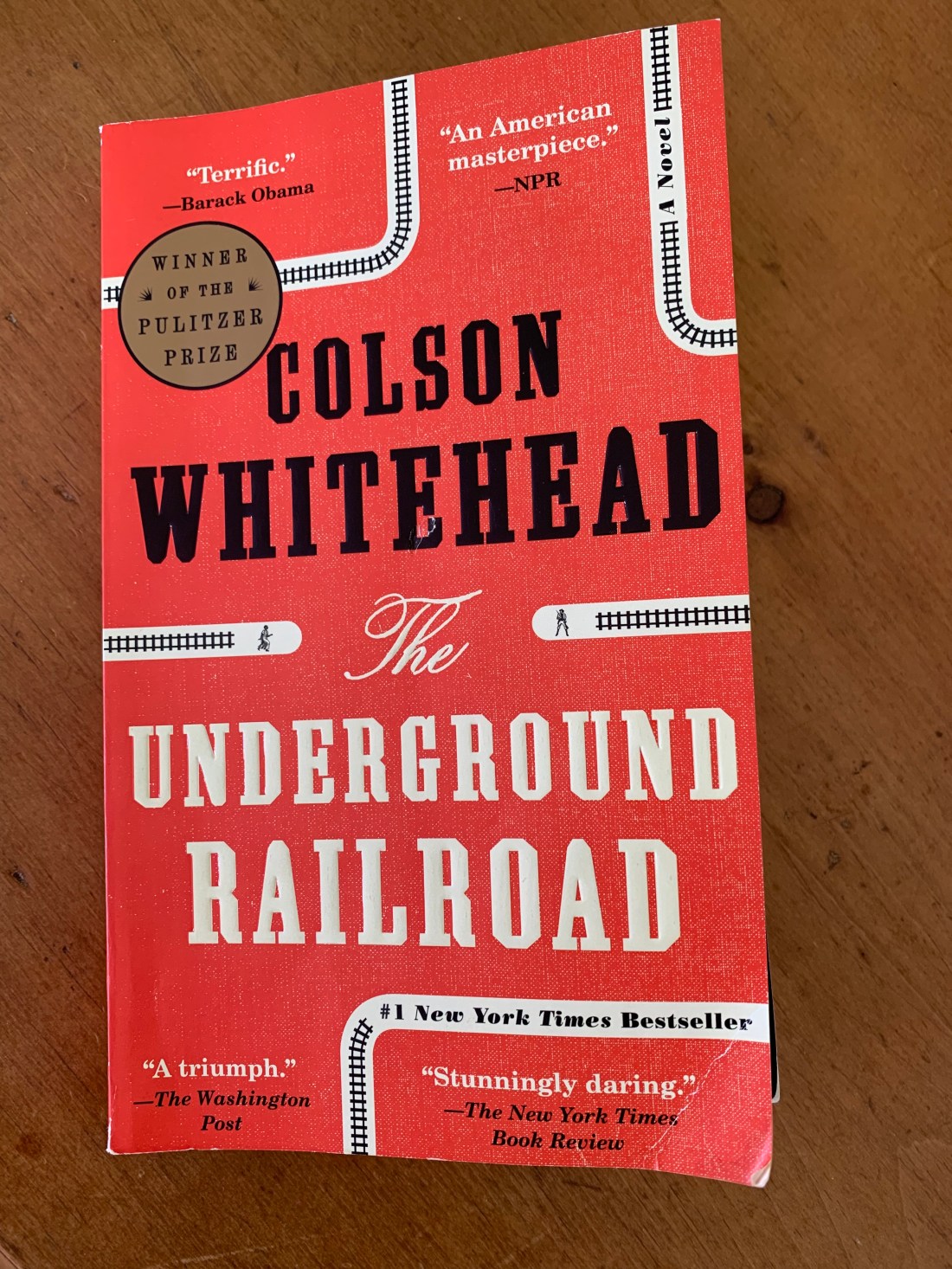

March 9, 2019: The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead

This book won the Pulitzer and the National Book Award (and about half a dozen other major awards) but it is also recommended by Oprah, Barack Obama and one of my best friends. So who could ask for more than that? The Underground Railroad tells the story of a runaway slave, Cora, and her flight through the Underground Railroad with one key difference – in Whitehead’s novel, the underground railroad isn’t a metaphor, it’s a series of secret tunnels and tracks that run beneath the lands of the South. This isn’t a novel I would have naturally gravitated towards but I am trying to expand my own reading life a little more and I’m interested to see how Whitehead combines history and fantasy to examine the antebellum era.

March 16, 2019: Where the Crawdads Sing by Delia Owens

This novel is set on the coast of North Carolina. In late 1969, a man is found dead and locals suspect “Marsh Girl”, a young woman who has survived for years alone in the marshes. The book jacket doesn’t give much more away but it was recommended to me by a co-worker who hasn’t steered me wrong yet, and it was one of Reese Witherspoon’s book club picks (Reese is a bit more hit and miss than my co-worker). It’s also a debut novel and I am a bit of a sucker for a good debut so I am looking forward to chasing some gray March skies away with this one.

March 23, 2019: Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi

Another debut, Homegoing begins in eighteenth-century Ghana. Two half sisters, Effia and Esi are born in different villages and fate takes them in very different directions: one marries an Englishman and lives in relative luxury in the notorious Cape Coast Castle, the other is captured by slavers and shipped off from the same castle to America to be sold into slavery. The novels follow the families of the sisters through eight generations and examines the impact of slavery on those who were taken and those who stayed. It made a lot of “best book of the year” lists in 2016 and since then several people have told me how much they loved it. It’s been on my shelf for a while so it’s time to read it, I think.

March 30, 2019: My Sister, the Serial Killer by Oyinkan Braithwaite

When I first heard about this novel on What Should I Read Next?, I couldn’t resist (damn you, Amazon app!) Here is the premise: the main character, Korede’s sister is beautiful and the favorite child. She might also be a serial killer who murders her boyfriends rather than just breaking up with them. And then Korede, the dutiful sister, must help her cover up her crimes. Korede is in love with a local doctor, but when he asks her for her sister’s number, she has to reckon with what her sister has become. Part thriller, part dark comedy My Sister, the Serial Killer was originally published in Nigeria and its yet another debut. I’m thinking a mix between a romantic comedy and Dexter?

I love the idea of having people tell you three books they love and one they hated. Listening to people tell you why they loved particular books is so much fun. Where do you get your book recommendations? If you’ve read any in this month’s line up, drop me a line and let me know! I’d ask for your recommendations but honestly, this To Read Pile is out of control.