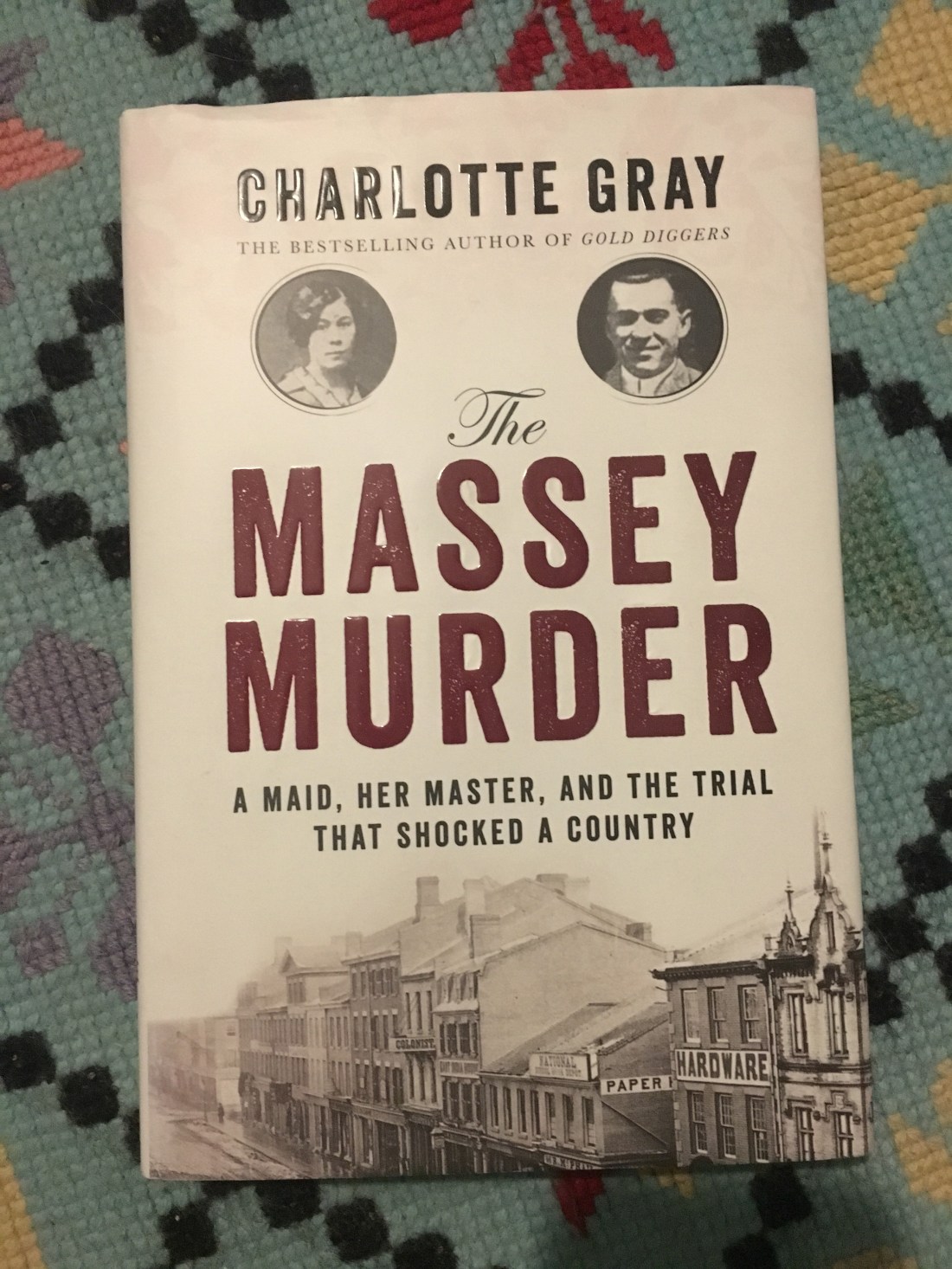

“In the early twentieth century, most women and men believed that, while men committed crime, women committed sins.” – Charlotte Gray, The Massey Murder

This book really surprised me. As a rule, I don’t really like reading non-fiction books about history. The writing is often dry, in my opinion. So this one has been sitting in my To Read Pile for a few years and I decided that as part of my challenge this year, I would push myself to read something I wouldn’t normally pick up. I blew the dust off The Massey Murder and I am so glad now that I did.

The book is written by Canadian historian and biographer, Charlotte Gray. It recounts the murder of Bert Massey (of that Massey family in Toronto) by his eighteen-year-old maid in 1915. The book is not really so much about the murder as the public reaction to the murder – Gray brings together a lot of factors to demonstrate why the trial of the maid, Carrie Davies, became a media sensation. Gray exposes the ways in which the trial brought to the surface so much of what was happening in Toronto society at the time: opinions about gender politics, class, immigration, the role of the media in shaping public perceptions of current events, the First World War (which was raging in Europe at the time) and the differences between the letter of the law and notions of justice. Through her research she was able to expose the relationship between business and political interests and the way news is reported. She demonstrates how people’s perceptions of women shaped their opinions of Davies’ innocence or guilt (despite irrefutable evidence that she did shoot and kill Massey). Despite the evidence, Davies would eventually plead not guilty on the grounds that Massey had allegedly attempted to rape her and she feared he would do it again – would her all-male jury agree that this was an act of self-defense despite the fact that Massey was returning home from work and unarmed when she shot him on his front step? Gray’s writing style is very engaging so her account unfolds like the plot of a good historical novel (although don’t be fooled, she has done her research).

What intrigued me most is that despite the fact that Gray is writing about a case that is now over 100 years old, our society is still debating so many of the same questions. When you consider the criticisms that our justice system does not serve the poor and marginalized, that women are still reporting sexual assaults at the hands of powerful male employers, that entanglements between media, politicians and business still allow people to question the validity of what is being reported, it almost seems that Gray could be writing about today. The context may have changed, but in many cases, the situation has not. The Massey Murder is a thought-provoking read, the story is so engrossing that I was looking forward to the chance to read it each night.

If you have read a really good historical book, drop me a line and let me know. Until next week, happy reading!