“We always live at least two lives, especially after a big decision: The life we decided on and the life we decided against. In our minds we let that other life play out, comparing it with our actual situation.” – Dirk Kurbjuweit, Fear.

Happy weekend everybody! This week’s book was an interesting one. Fear is a German novel that poses the question: how far would you go if you were afraid for your family? Randolf Tiefenthaler, the narrator, is a relatively successful architect in Berlin. He has an intelligent and entertaining wife, Rebecca, two children and lives in a nice ground-floor flat. He thinks of himself as a law-abiding citizen, someone who values law over disorder, intellect over action, words over force: a modern man.

The novel unfolds as Randolf records the events that led up to his father being found guilty of manslaughter in the death of Dieter Tiberius. A man who grew up in the foster system and is essentially a shut-in, Tiberius lived in the flat below the Tiefenthalers and became obsessed with Rebecca. He writes letters and poems that both threaten and disgust the Tiefenthalers; he accuses them of abusing the children, he calls the police on them repeatedly. He watches Randolf’s children when they play outside on their trampoline. He peers in their windows at night. The Tiefenthalers become increasingly afraid for themselves and their children. What if Tiberius does something to the children? What if the police believe his stories? The problem is, despite terrorizing the family, Tiberius has not broken any laws – the lawyers, the police, and their landlord claim that their hands are tied. Until Tiberius breaks the law, there is no one who can help the Tiefenthalers.

The situation forces Randolf to reevaluate himself and his life. He had long written off his father and brother (neither of whom are opposed to violence) as being lesser. As Tiberius continues to harass the family, Randolf questions himself as a father, a husband and ultimately a man. As a young person he rejected his father’s enthusiasm for guns and his brother’s preference for solving problems with his fists. He put his faith in law and logic. But then the law fails. Not knowing what else to do, Randolf turns to his father, knowing what he is asking him to do. When the story begins, Tiberius is dead and Randolf’s father is serving a jail sentence for his killing.

The author forces the reader to confront a lot of questions about morality throughout the novel. Dieter Tiberius is the obvious villain but Randolf and Rebecca are flawed as well, they have characteristics that are not very appealing: Randolf lies to his wife and shirks his family responsibilities, Rebecca throws screaming fits. Their marriage is falling apart. And then Tiberius comes into their lives and somehow they become better people – and worse – because of their experiences with him. They pull together as a family in a way that was unlikely before the harassment began: and then the characters must ask themselves, what does it mean if the good you experience in your life is a direct consequence of the evil? How far would you go to protect that goodness?

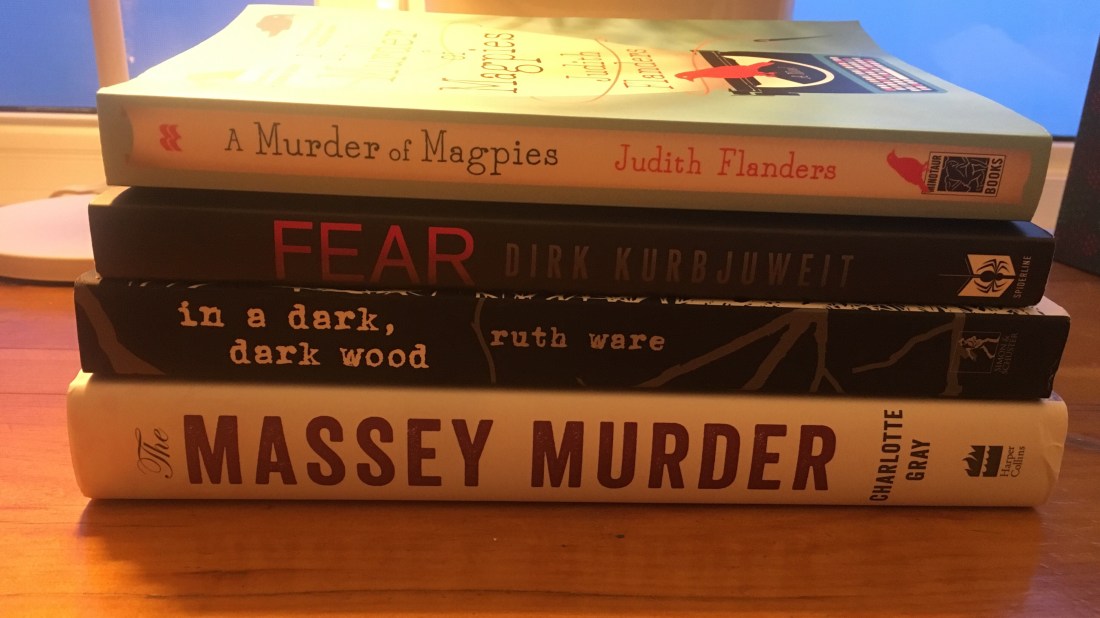

I think this novel is really much more intellectual that the genre would lead readers to expect. It is a thriller but the fear isn’t so much driven from the plot, but from the kinds of questions it poses: what would you do if your spouse was threatened? Your children? What kind of person does it make you if you couldn’t make yourself do what it took to protect them? Dieter Tiberius is like a nightmare figure – the threat he poses is the fear he creates in the characters’ minds. For me, this was a much more satisfying book than last week’s in a dark, dark wood. The way the narrative is structured make it feel very real, like this was something that could happen to anyone at any time. That is what makes it so compelling as a reader because as Randolf questions his decisions and tries to make sense of what happened, the reader can’t help but ask themselves the same questions.

If you read Fear, drop me a note and let me know what you think. Until next week, happy reading!